How Does Schedule Difficulty Vary by Team?

No two teams have the same schedule. How much can they vary, and how much does this matter?

In my previous post, I looked at all schedules for each team in the past 20 seasons. The context for this was that I wanted to see if 2023 had a more even distribution of schedule difficulty as a result of the league-wide change schedule that season–that for the first time in MLB's recent history, every team got to play every other team at least once in a single season.

Since the previous post is linked above, I won't go too into detail with my discoveries and conclusions regarding the 2023 schedule specifically. But in the process of researching and writing that post, I realized how useful this dataset was. Since it was organized by season by team, I could take a much closer look at how schedule strength varies in the league. In other words, I could write another post.

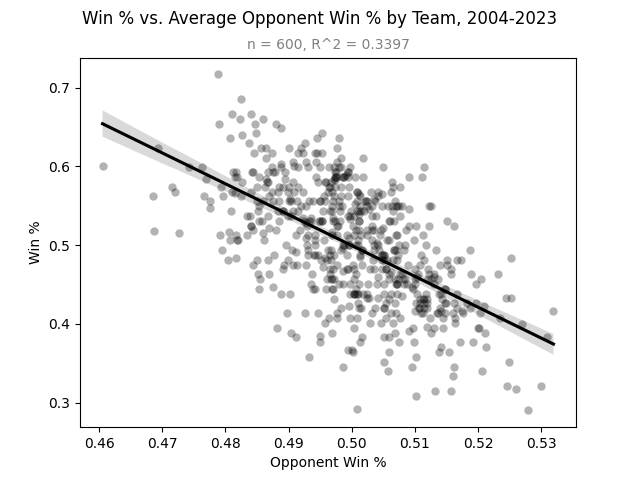

Schedule strength as a concept is a topic that has long interested me, even prior to my last post. Adjustments made based on schedule strength are baked into both my projection system and various stats in the daily leaderboard. However, it seems like a topic in baseball analytics that's been largely ignored by most other sources in favor of other adjustments (e.g. park factors). But is that really fair? I looked at the same dataset as last time to find out, which can be found here1. Using that, I then plotted a very simple linear regression between both winning percentage and average opponent winning percentage for every MLB team-season since 2004:

There is a clear negative correlation between a given team's winning percentage and their average opponent winning percentage.

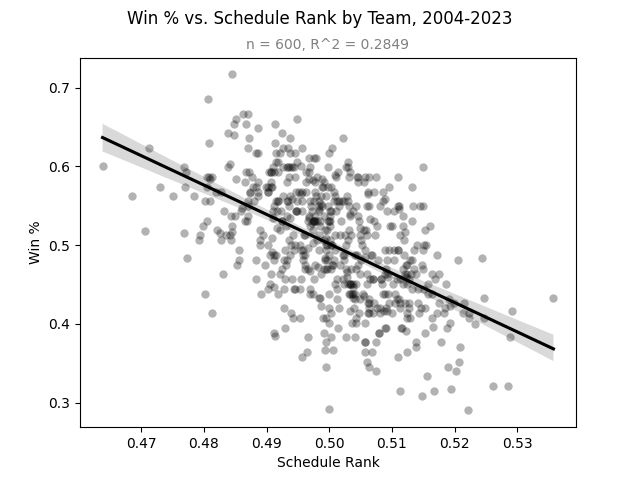

As you can see above, the regression between winning percentage and opponent winning percentage shows a clear negative relationship: the more difficult a given team's opponents are, the worse the team does, on average. However, the average winning percentage of opponents is not the only metric we can use. In my previous post, I also used a metric which I called "opponent skill," which is the average opponent Pythagorean winning percentage, and which I will call "schedule rank" here2. Plotting that against winning percentage, we get the following:

The graph of schedule rank vs. winning percentage is virtually indistinguishable from the one above it.

This shows that the first graph is no fluke. There is a clear negative correlation between how well a team plays and how well their opponents play. That being said, I don't feel comfortable saying that schedule strength necessarily determines a team's performance–correlation doesn't equal causation, after all. I think a big reason for why this correlation exists is that teams simply don't play themselves. What I mean is that if you're a bad team, then your opponents will be better than you on average by definition, no matter how your schedule is set up (and of course, the opposite is true for good teams).

However, I don't think causation is completely lacking either. I can't help but wonder if there were any potentially good teams stunted by an unusually tough schedule, or any relatively weak teams pushed over the edge by an unusually easy one. I therefore decided to look at all 600 individual team-seasons since 2004 and rank them from hardest season schedule to easiest, as measured both by opponent winning percentage and schedule rank.

Top 10 Hardest Team Schedules by Opponent W% (2004-2023)

| Rank | Team | Season | Opponent W% |

| 1[^3] | D-backs | 2020 | .5319 |

| 2 | Royals | 2006 | .5309 |

| 3 | Orioles | 2021 | .5298 |

| 4 | Orioles | 2018 | .5279 |

| 5[^3] | Red Sox | 2020 | .5269 |

| 6[^3] | Pirates | 2020 | .5260 |

| 7[^3] (tie) | Giants | 2020 | .5253 |

| 7[^3] (tie) | Rockies | 2020 | .5253 |

| 9 | Marlins | 2019 | .5249 |

| 10 | D-backs | 2021 | .5246 |

Top 10 Hardest Team Schedules by Schedule Rank (2004-2023)

| Rank | Team | Season | Schedule Rank |

| 1[^3] | Rockies | 2020 | .5358 |

| 2[^3] | D-backs | 2020 | .5292 |

| 3 | Royals | 2006 | .5289 |

| 4 | Orioles | 2021 | .5285 |

| 5 | D-backs | 2021 | .5262 |

| 6 | Orioles | 2010 | .5247 |

| 7[^3] | Royals | 2020 | .5246 |

| 8[^3] | Giants | 2020 | .5243 |

| 9[^3] | Red Sox | 2020 | .5232 |

| 10 | Rays | 2007 | .5223 |

The number of teams on this list from the pandemic-shortened 2020 season is no coincidence. I decided to keep 2020 in my analysis to make a point: when it comes to schedule analysis, sample size is everything. If a team has an overall easy schedule, you can almost certainly find some 60-game sample that is tougher than average, and vice versa. Regardless, most of the teams in the list, especially from outside of 2020, were relatively hapless and a change in schedule would almost certainly not have saved them. Baltimore in 2018, for example, would likely remain well under .500 in a schedule-neutral environment, using the regression above–nowhere near well enough to compete, especially with that year's AL East. In contrast, consider the 2020 Diamondbacks–they had a not-terrible winning percentage of .417 in a 60-game season, and if they'd faced a perfectly neutral schedule, would have had a winning percentage likely in excess of .500–more than enough for a wild card spot that season. Instead, they finished 25-35 and dead last in the NL West–in no small part due to the strength of their opponents.

Now, let's look at the easiest team schedules in the same sample, as measured by both average opponent winning percentage and schedule rank.

Top 10 Easiest Team Schedules by Opponent W% (2004-2023)

| Rank | Team | Season | Opponent W% |

| 1[^3] | Athletics | 2020 | .4606 |

| 2 | Guardians | 2018 | .4685 |

| 3[^3] | Cardinals | 2020 | .4687 |

| 4 | Twins | 2019 | .4712 |

| 5 | Guardians | 2019 | .4715 |

| 6 | Twins | 2004 | .4720 |

| 7 | Cardinals | 2006 | .4727 |

| 8 | Nationals | 2017 | .4743 |

| 9 | Reds | 2012 | .4763 |

| 10 | Reds | 2014 | .4767 |

Top 10 Easiest Team Schedules by Schedule Rank (2004-2023)

| Rank | Team | Season | Schedule Rank |

| 1[^3] | Athletics | 2020 | .4638 |

| 2 | Guardians | 2018 | .4685 |

| 3[^3] | Cardinals | 2020 | .4712 |

| 4 | Twins | 2019 | .4730 |

| 5 | Guardians | 2019 | .5262 |

| 6 | Reds | 2010 | .4751 |

| 7 | Nationals | 2017 | .4768 |

| 8[^4] | Cardinals | 2006 | .4768 |

| 9 | Cardinals | 2022 | .4770 |

| 10 | Braves | 2013 | .4771 |

Like before, we can see a large number of teams from the shortened 2020 season pop up here. This time, though, I'd like to focus my analysis on two teams on this list from different seasons: the 2018 Cleveland and 2006 St. Louis. The former won a famously-weak AL Central with a 91-71 record, equating to a winning percentage of .562. Against a perfectly-neutral batch of opponents, and with exactly the same quality of play, this Cleveland team likely would have had a winning percentage in the mid-.400s range–nowhere near good enough to win any division. The latter, however, is an even more interesting case. In 2006, the Cardinals stumbled across the finish line first in the NL Central with a record of 83-78, equating to a winning percentage of .516. In a perfectly fair world, their play would have netted them a winning percentage around the low .400s range. But in reality, they made the playoffs, won the National League pennant, and lo and behold, won the World Series. The 2006 Cardinals were already somewhat infamous for being potentially the weakest championship team in recent memory, but this only adds fuel to the fire.

On the topic of divisions, I also decided to sort each team in the league by division, and see where all division-seasons since 2004 stack up against each other.

Top 10 Hardest Divisions by Avg Opponent W% (2004-2023)

| Rank | Division | Season | Opponent W% |

| 1 | AL East | 2008 | .5142 |

| 2 | AL West | 2006 | .5127 |

| 3 | AL East | 2012 | .5121 |

| 4 | AL West | 2009 | .5112 |

| 5[^3] | NL West | 2020 | .5111 |

| 6 | AL Central | 2006 | .5102 |

| 7 | AL East | 2013 | .5095 |

| 8 | AL East | 2010 | .5091 |

| 9 | AL West | 2012 | .5090 |

| 10 | AL Central | 2015 | .5081 |

Top 10 Hardest Divisions by Avg Schedule Rank (2004-2023)

| Rank | Division | Season | Schedule Rank |

| 1 | AL East | 2008 | .5146 |

| 2[^3] | NL West | 2020 | .5135 |

| 3[^3] | AL West | 2005 | .5135 |

| 4 | AL East | 2012 | .5111 |

| 5 | AL East | 2015 | .5107 |

| 6 | AL West | 2006 | .5105 |

| 7 | AL Central | 2006 | .5103 |

| 8 | AL West | 2014 | .5098 |

| 9 | AL East | 2007 | .5095 |

| 10 | AL East | 2016 | .5092 |

These lists surprised me for two reasons. Firstly, I expected to see the AL East in the past couple years (say, 2022 and 2023) show up here, if not top the lists altogether. I guess my assumption might have been affected by recency bias, though. (For what it's worth, both the 2022 and 2023 AL East were just outside the top 10 on both lists.) Interestingly, however, we do see an AL East season atop this list–namely in 2008, when every team except the Orioles had at least 86 wins. The Rays managed to finish first in the division for the first time in team history, and ended up making the World Series, despite only winning 66 games the season prior. The other interesting fact I noticed is that only one National League division shows up on either list–the 2020 NL West. This is extremely interesting–so much so that I decided to perform a quick statistical test. Since the percentage of total divisions in this sample that are in the National League is 50 percent, then the probability of only seeing 1 NL division in a random sample of 10 is only about 1 percent3. All that's to say, the lack of NL presence on these two lists is probably no coincidence. As for why this is the case, I have a couple of ideas, but I will have to save those for another time.

Now, let's look at the other side of the list: the easiest divisions to compete in since 2004.

Top 10 Easiest Divisions by Avg Opponent W% (2004-2023)

| Rank | Division | Season | Opponent W% |

| 1 | AL Central | 2018 | .4843 |

| 2 | NL West | 2008 | .4853 |

| 3[^6] | NL Central | 2006 | .4853 |

| 4 | AL Central | 2019 | .4859 |

| 5 | NL West | 2005 | .4863 |

| 6 | NL East | 2015 | .4875 |

| 7 | NL Central | 2012 | .4885 |

| 8[^3] | AL West | 2020 | .4889 |

| 9 | NL Central | 2009 | .4892 |

| 10 | NL East | 2021 | .4893 |

Top 10 Easiest Divisions by Avg Schedule Rank (2004-2023)

| Rank | Division | Season | Schedule Rank |

| 1 | NL West | 2005 | .4818 |

| 2 | AL Central | 2019 | .4864 |

| 3 | NL West | 2008 | .4869 |

| 4 | NL Central | 2006 | .4878 |

| 5[^7] | AL Central | 2018 | .4878 |

| 6[^3] | AL West | 2020 | .4882 |

| 7 | NL Central | 2009 | .4885 |

| 8 | NL Central | 2007 | .4887 |

| 9 | NL East | 2015 | .4897 |

| 10 | NL Central | 2010 | .4905 |

Atop the first list, using average opponent winning percentage, we see the famously weak 2018 AL Central mentioned earlier. The distribution of divisions across the two leagues is markedly more even here, with 7 NL divisions and 3 AL divisions in either list, as opposed to the 9 and 1 respectively we saw before. Atop the second list, using schedule rank, we see the 2005 NL West–where the division winner, San Diego, only had an 82-80 record. That's like if the 2023 Yankees won the AL East–which as a Yankees fan is a pretty mind-melting thought. Interestingly, that same year, the NL East saw every team at .500 or greater–the Braves won with a 90-72 record, and the fifth-place Nationals were only 9 games behind. I guess all those lost NL West wins had to go somewhere.

With all this in mind, I think it's fair to say the following: 1) there is a tangible correlation between team schedule strength and team performance, and 2) there are numerous instances where schedule strength can have a noticeable effect on team performance, and 3) schedule strength can vary significantly by division, even within a given league in the same season. Of course, an easier or tougher schedule does not inherently cause a team to do good or bad–but to suggest that it has no impact whatsoever in any case is just as ignorant.

I am very glad I got to revisit the subject of schedule strength, especially on a more team-based scale. In the future, I'd like to further investigate the variation in schedule strength by division and by league–my earlier finding about AL divisions evidently being tougher warrants further investigation. I don't know when that will be, though, since the season is about to start up and I need to prepare the projection and leaderboard systems accordingly. Regardless, I'm glad to get back into the baseball analytics grind—so expect more from me to come.

Footnotes

- Note: All data in this post is sourced from Fangraphs and Baseball Reference unless otherwise noted ↩

- I will talk about the reason for this in a future post. For now though, just know it's interchangeable with average opponent Pythagorean winning percentage ↩

- 1.074 percent, to be exact. Based on a binomial distribution with p = 0.5, n = 10, and x = 1 ↩